The Clabburn Family of Norwich

Notes by

John Barnard

Updated 28 February 2023

| Clabburn Family Tree (18th-20th centuries) |

| Catalogue of Clabburn source material |

My maternal grandmother, Ethel de Pearsall James, née Clabburn, was descended from a Norwich family which, for several generations, had been involved in that city's weaving trade, rising during the 19th century to considerable prosperity and business success. Daughters married into the families owning the well-known firms of both Crosse & Blackwell and Swan & Edgar, though some of the sons were less fortunate and affluent, and there was at least one "black sheep", the discovery of whose history has been one of the more intriguing aspects of my research.

There were quite a lot of Clabburns (with various spellings) in Norwich in the 18th and 19th centuries, who may or may not have been related, but the family tree here shows the descendants of my direct ancestor Thomas Clabburn I (c. 1762-1824). Some secondary sources (including http://airgale.com.au/clabburn/ and CLA/1/10) show a couple of generations before him, but they are somewhat inconsistent, and I have not yet evaluated the relevant primary sources for those earlier Clabburns.

Thomas Clabburn I (c. 1762-1824): weaver

Thomas Clabburn (c. 1762-1824) is described in a Norwich trade directory of 1783 as a "worsted weaver", and as a "manufacturer of bed coverlids at 16 Timberhill Street" [CLA/2/1]. In 1785 he married Sarah Houghton (c. 1768-1833) and they had three sons. The youngest, Robert Clabon (as the name is spelt in the parish register), was born on 20 July 1793 and baptised the next day at St Paul's Church; he is probably the "Robert Clabourn, son of Thomas and Sarah", who died in St Paul's parish but was buried at St Augustine's the day after - interestingly he is described in the parish register as a pauper. Their elder two sons, however, lived out their full threescore years and ten. William Clabburn (1785-1861) is described as a shawl weaver on the letters of administration granted to his nephew for his modest estate of less than £100, but his brother Thomas Clabburn II (1788-1858) became a rich and successful businessman, presiding over one of the major firms manufacturing the famous "Norwich shawls".

Thomas Clabburn II (1788-1858): manufacturer of Norwich shawls

Norwich shawls were

developed

from the traditional worsted

cloth which had been woven in Norwich for hundreds of years (the name

is taken from the village of Worstead near Norwich), under the

influence of the Kashmiri ("cashmere") shawls imported from Britain's

Indian empire from the end of the 18th century. Using a silk warp and

worsted weft, they could be produced much more cheaply than the

imports, but using copies of the Indian designs.

Many small manufacturers started making them as demand rose in the

early 1800s, but fierce competition ensured that by the middle of the

century only a handful of established firms remained [CLA/27]; one of

these was Clabburn Sons

& Crisp, a business set up in 1846 by Thomas

Clabburn with

two of his sons, William

Houghton Clabburn I (1820-1889) and Thomas

Clabburn III (1824-1880),

along with Thomas Dawson

Crisp

(1809-1878) [CLA/9].

The Great Exhibition of 1851, with over six million visitors between

May and October, provided a splendid marketing opportunity, which the

firm did not hesitate to exploit. An engraving in its "Illustrated

'Cyclopaedia" showed

Norwich shawls were

developed

from the traditional worsted

cloth which had been woven in Norwich for hundreds of years (the name

is taken from the village of Worstead near Norwich), under the

influence of the Kashmiri ("cashmere") shawls imported from Britain's

Indian empire from the end of the 18th century. Using a silk warp and

worsted weft, they could be produced much more cheaply than the

imports, but using copies of the Indian designs.

Many small manufacturers started making them as demand rose in the

early 1800s, but fierce competition ensured that by the middle of the

century only a handful of established firms remained [CLA/27]; one of

these was Clabburn Sons

& Crisp, a business set up in 1846 by Thomas

Clabburn with

two of his sons, William

Houghton Clabburn I (1820-1889) and Thomas

Clabburn III (1824-1880),

along with Thomas Dawson

Crisp

(1809-1878) [CLA/9].

The Great Exhibition of 1851, with over six million visitors between

May and October, provided a splendid marketing opportunity, which the

firm did not hesitate to exploit. An engraving in its "Illustrated

'Cyclopaedia" showed

a rich cashmere shawl manufactured by this firm in Norwich which we understand was purchased by the Queen. It is the first attempt in Norwich at shawl weaving on a Jacquard loom. For fineness of texture, variety and beauty of colours and elegance of pattern it cannot be surpassed.

A portrait of Thomas was commissioned from the Pre-Raphaelite artist Frederick Sandys by Thomas's eldest surviving son William Houghton Clabburn I, but the current whereabouts of the original are unknown. The art historian Betty Elzea included it in her 2001 catalogue raisonné of Sandys' work [CLA/29, no. 1.A.85], after seeing a sepia photograph of it in the collection of Michael Clabburn (1947-2004), a great-great grandson of Thomas's other surviving son Thomas Clabburn III [CLA/1/6]. In a 1989 letter to Michael Clabburn [CLA/1/7] she wrote that it appeared "to be a chalk or pastel drawing and almost certainly is by Sandys, done in the 1850s, judging by the style. The appearance of the sitter agrees with Thomas's age at that time". Since then, I have come across another photograph of the portrait [CLA/43/5] (shown right), with a note that it may have been acquired by Charles Clabburn (1881-1965), a grandson of William Houghton Clabburn I's, from his father Arthur's old nannie. Charles emigrated to New Zealand, and it is possible that the original portrait may be there, though I have not yet tried to trace it.

Thomas was clearly much admired within the city, and probably employed many local weavers as independent contractors. On his death in 1858 a tablet was erected in St Augustine's Church in Norwich, which reads:

This tablet is erected to the memory of Thomas Clabburn, manufacturer, by upwards of six hundred of the weavers of Norwich and assistants in his establishment, as a mark of esteem for his many virtues as an employer and a kind good man. He departed this life March 31st 1858, aged 70. [CLA/1/8]

He is buried in a tomb in the churchyard at St Augustine's along with his wife and his parents.

Thomas married Elizabeth Dann (1786-1862 - in some sources and transcriptions her name is spelt Denn, or even Dunn) on 23rd January 1809 at St Martin's Church in Norwich; he was 21 and she was 22. Over the next 24 years they produced eleven children, seven of whom lived into adulthood, and there is some repeat usage of the names of those who died young. Their youngest daughter, another Elizabeth (1833-1917), was born less than a month before her mother reached her 47th birthday - a remarkable achievement for the 1830s.

Two of her sons commissioned portraits of her. That by Frederick Sandys [CLA/29 no. 2.A.29] (above left) was commissioned by William in 1861, when she was 75, while the following year (the year she died) his brother Thomas III commissioned one from an artist called Charles Croft [CLA/44/1] (above centre). The Sandys portrait is now in the Norwich Castle Museum, while the Croft one has passed to Thomas III's great-great grandson Tom Rivière. There is also a photograph of her in Michael Clabburn's collection [CLA/1/8] (above right).

All four of Thomas and Elizabeth's surviving daughters married prosperous and successful businessmen, and produced families:

- Sarah Clabburn (1811-1872) married Richard Parkinson (c. 1806 - before 1871) who owned property in Manchester, where they lived; in the 1871 census she is shown as a widow with "income from horses". They had at least two children.

- Ann Frances Clabburn (1826-1894) married John Bishop (1821-1887), joint proprietor of the Norwich Ironworks company Barnard, Bishop and Barnards Ltd. [CLA/39], and had five children. John Bishop's business partners, Charles Barnard and his two sons, are not related to my own Barnard family.

- Amelia Clabburn (c. 1829 - 1905) married Jeremiah Dummett (c. 1818 - 1900), a tea and coffee merchant. They had three children and lived at 54 Porchester Terrace in London; when he died his estate was valued at more than £70,000 (equivalent to about £10 million in today's values).

- Elizabeth Clabburn (1833-1917) married John Swayne Pearce (c. 1829-1918), a silk mercer and draper who, in 1886 became the first Chairman of the Board of the newly amalgamated firm of Swan & Edgar Ltd, the upmarket drapers and department store whose famous shop on Piccadilly Circus finally closed (after many changes of ownership) as recently as 1982. They had eight children.

Of the three surviving sons, my great-great-grandfather William Houghton Clabburn I (1820-1889) and Thomas Clabburn III (1824-1880) carried on their father's business after his death in 1858, while Robert George Clabburn (c. 1828 - 1863) had a rather more chequered career, discussed below.

William Houghton Clabburn I (1820-1889): manufacturer and art patron

William was the eldest surviving son of Thomas Clabburn II,

and in his youth he was "a man of powerful physique ... and as

an oarsman had few equals" [CLA/35].

There are reports in the Norfolk Chronicle of his involvement in

amateur rowing races in Norwich in 1841 and 1842 [CLA/42].

The report for the latter gives his weight as 11st 7lb (73kg), rowing

number 3 in a coxed four against Kings College London. There was

obviously a family interest in rowing, as the stroke position in that

boat was taken by his younger (and lighter) brother Thomas Clabburn III

(9st 2lb). It is interesting that rowing prowess has also been shown by

several of William's descendants: his youngest son Henry was

stroke for his Cambridge College, while great-grandson Robert

Clabburn Trevenen James

(1917-2008)

rowed for his Oxford college and great (x3) grandson Richard Ian

Clabburn Harrisson

(1984-2019) for Imperial College; the laurel probably goes to great

(x2) grandson Phillip Wilkinson (b. 1947) who

rowed stroke

in the Australian Eight at the 1972 Munich Olympics.

William was the eldest surviving son of Thomas Clabburn II,

and in his youth he was "a man of powerful physique ... and as

an oarsman had few equals" [CLA/35].

There are reports in the Norfolk Chronicle of his involvement in

amateur rowing races in Norwich in 1841 and 1842 [CLA/42].

The report for the latter gives his weight as 11st 7lb (73kg), rowing

number 3 in a coxed four against Kings College London. There was

obviously a family interest in rowing, as the stroke position in that

boat was taken by his younger (and lighter) brother Thomas Clabburn III

(9st 2lb). It is interesting that rowing prowess has also been shown by

several of William's descendants: his youngest son Henry was

stroke for his Cambridge College, while great-grandson Robert

Clabburn Trevenen James

(1917-2008)

rowed for his Oxford college and great (x3) grandson Richard Ian

Clabburn Harrisson

(1984-2019) for Imperial College; the laurel probably goes to great

(x2) grandson Phillip Wilkinson (b. 1947) who

rowed stroke

in the Australian Eight at the 1972 Munich Olympics.

William became a partner in the family firm of Clabburn, Sons & Crisp from 1846 (when he was 26) and seems to have taken an increasingly dominant role as the business expanded during the 1850s, especially following the success of the Great Exhibition in 1851. In 1854 he filed a patent (No. 1750) for improvements in the manufacture of shawls, and the following year seventy weavers are recorded as working for the firm [CLA/27].

It was presumably also around this time that William first befriended the artist Frederick Sandys (1829-1904) and over the next two decades he commissioned several paintings from him, including a number of portraits of members of his family, some of which are now in the Norwich Castle Museum, though unfortunately not on display. A major exhibition of Sandys' work, including most of the Clabburn portraits, was shown in Brighton and in Sheffield in 1974 [CLA/20]. It was curated by Betty O'Looney who, under her married name of Betty Elzea, published a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Sandys' work in 2001 [CLA/29]. Though not a formal member, Sandys was associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by the artists Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. William also commissioned Rossetti to produce an oil replica of his Mary Magdalen at the Door of Simon the Pharisee [CLA/37].

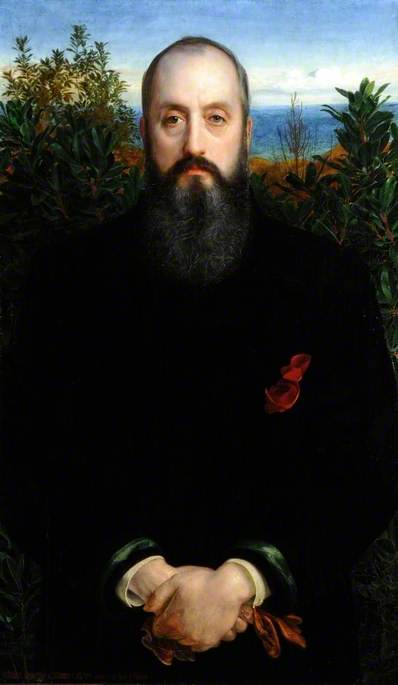

Sandys' oil portrait of William himself [CLA/29, no. 3.7], shown right, is now at Sheffield City Art Galleries, and though it was on display in the Mappin Gallery there in the early 1980s, it has not been shown for many years. Sandys himself felt that it was "nobler in purpose than anything I have yet done", but The Observer's art critic considered it "so studiously stiff in treatment as to be scarcely amenable to criticism". It dates from 1870, when William was 50, and perhaps it reflects the upright stiffness of a successful Victorian businessman. There is also a preliminary study for this portrait [CLA/29, no. 3.6], in chalk, which is now at Norwich Castle Museum.

When William's father Thomas Clabburn II died in 1858 his Will [CLA-9] gave William "full power to continue and carry on" the business, and to that end bequeathed to him "all my capital and stock in trade ... belonging to the said trade or business". Though there were also specific legacies to William's sisters and brother Thomas Clabburn III, William was clearly left in charge, and it is not clear what role Thomas III continued to play in the business after their father's death.

The same year William purchased Sunny Hill, a house in Thorpe (possibly previously known as Holly Hill), where he lived with his growing family. In the early 21st century the house formed part of Thorpe House Langley Preparatory School, and I had some correspondence with a teacher there in 2014. The school moved out in 2016, and its main building (Beech House) was destroyed by fire in June 2018; I am not clear as to the fate of Sunny Hill. Sandys is actually recorded as a visitor there in the 1871 census, and he probably used a boathouse adjoining the nearby Walpole House on Yarmouth Road (to which William moved in 1879) as a studio. In the 1990s my uncle Bob James corresponded with the then owner of Walpole House, Mrs Margaret Langley, who was very interested in the history of the house, and its connections with Clabburn and Sandys [CLA/3/5].

According to Julie-Joy Hermann, the daughter of Garth Clabburn (1917-1983 and one of Arthur Clabburn's grandsons), when her father established a sheep station in Victoria, Australia, after the Second World War, he named it Sunninghill after the village in Berkshire, which he had visited while on leave in England in 1941, rather than as a reference to his ancestral family home in Norwich. A possible reference to both names is provided by Garth's two granddaughters, Sophie and Celeste Clabburn, who perform as the successful Australian country-and western duo The Sunny Cowgirls.

![Photograph of W.H. Clabburn [CLA/45] Photograph of W.H. Clabburn [CLA/45]](docs/CLA_Docs/CLA-45%20WH%20Clabburn%20Photo.jpg) William was by this time very

much one of "the great

and the good" in Norwich; he was a local magistrate and in 1866-7 he

served a term in the honorary position of Sheriff of the

city. There were more successes at the International Exhibition in

London

in 1862 (a gold medal, for shawls of superior quality [CLA/27]), and in

exhibitions in Paris in 1867 (William was a Juror [CLA/25], and

there is a prize medal at the Bridewell Museum in Norwich [Accession

no. NWHCM:1914.99.2]) and

again in London in 1871. But

by the 1870s fashions were changing, mass-produced

shawls from Paisley were flooding the market, and demand for Norwich

shawls was declining. When the non-family partner in the firm, Thomas

Dawson Crisp, died on 2 Sep 1878 the partnership was formally

dissolved. Nevertheless, the development of the Victorian passion for

correct mourning etiquette provided excellent business opportunities

for the Norwich Crape Company [CLA/40],

which made the black crape used for

mourning wear. William had helped to found the company in 1856 and was

Chairman of the Board from 1876 to 1888 [CLA/27];

the company was not finally wound up until 1925.

William was by this time very

much one of "the great

and the good" in Norwich; he was a local magistrate and in 1866-7 he

served a term in the honorary position of Sheriff of the

city. There were more successes at the International Exhibition in

London

in 1862 (a gold medal, for shawls of superior quality [CLA/27]), and in

exhibitions in Paris in 1867 (William was a Juror [CLA/25], and

there is a prize medal at the Bridewell Museum in Norwich [Accession

no. NWHCM:1914.99.2]) and

again in London in 1871. But

by the 1870s fashions were changing, mass-produced

shawls from Paisley were flooding the market, and demand for Norwich

shawls was declining. When the non-family partner in the firm, Thomas

Dawson Crisp, died on 2 Sep 1878 the partnership was formally

dissolved. Nevertheless, the development of the Victorian passion for

correct mourning etiquette provided excellent business opportunities

for the Norwich Crape Company [CLA/40],

which made the black crape used for

mourning wear. William had helped to found the company in 1856 and was

Chairman of the Board from 1876 to 1888 [CLA/27];

the company was not finally wound up until 1925.

Politically William was a Liberal (though on the Whig side of the party, rather than the Radicals') but did not participate actively in meetings. He took an interest in local charities, most notably the Norwich Blind Asylum (now Vision Norfolk), and his business abilities also earned him a place on the Board of the Norwich Union Life Assurance Society (now part of Aviva plc), where he remained until his death in 1889 [CLA/35].

William

married Hannah Louisa

Blyth (1824-1878) in 1846, and

Sandys provided two portraits of her. The first of them, dating from

1860, when she was 36, is in oils [CLA/29, no.

2.A.4] (left) and was particularly admired by Rossetti. The second is a

chalk drawing from nine years later [CLA/29, no.

2.A.124] (right). Both portraits are now at the Norwich Castle Museum.

William

married Hannah Louisa

Blyth (1824-1878) in 1846, and

Sandys provided two portraits of her. The first of them, dating from

1860, when she was 36, is in oils [CLA/29, no.

2.A.4] (left) and was particularly admired by Rossetti. The second is a

chalk drawing from nine years later [CLA/29, no.

2.A.124] (right). Both portraits are now at the Norwich Castle Museum.

The couple had six children, listed below, most of whom also had their portraits painted or drawn by Sandys.

- William Houghton Clabburn II (1848-1905) emigrated to New Zealand and married Harriet Mottlee there in 1871, though the stipulations in his father's Will, discussed below, suggest that his father may not have had that much faith in his financial prudence, as they allowed him only a life-interest in a legacy of £500 (and that only so long as he was not bankrupted), with the capital reserved for his children. In fact William and Harriet seem to have had just one son, William Houghton Henry Clabburn (1878-1951) who himself left three daughters, thus extinguishing the Clabburn surname in this branch of the family. Nevertheless his descendants appear to be still living in Southland, New Zealand, and his grandson Edward Arnold ("Ted") Winsloe (1931-2001) was a successful racehorse trainer, a tradition which his family continues to this day; I am endeavouring to establish contact with them.

Arthur

Edward Clabburn

(1849-1901), my great-grandfather, spent a

few years in the army (where this photograph was taken) before pursuing

a career as a freelance artist,

under the influence of his father's friend Frederick Sandys.

He

married Rosey

de Pearsall (c.1861-1922), grand-daughter of the composer Robert Lucas

Pearsall.

Arthur

Edward Clabburn

(1849-1901), my great-grandfather, spent a

few years in the army (where this photograph was taken) before pursuing

a career as a freelance artist,

under the influence of his father's friend Frederick Sandys.

He

married Rosey

de Pearsall (c.1861-1922), grand-daughter of the composer Robert Lucas

Pearsall.

Mary

Louisa Clabburn (1850-1886) married

Edmund Meridith Crosse

(1846-1918) of the Crosse & Blackwell tinned

food manufacturing firm,

and had five children. Mary died just three years after giving birth to

their younger son Edmund

Mitchell Crosse (b. 1883), who later married Leda Roumieu,

grand-daughter of the architect R. L. Roumieu (1814-1877). Roumieu

had designed warehouses for the Crosse and Blackwell firm and Leda's

aunt

Emilie Isabella Roumieu (1852-1929) had been an early love of Mary

Louisa's elder brother Arthur's [CLA/16],

though she had gone on to marry (and subsequently divorce, on grounds

of

adultery and violence) Alexander Coghill Wylie. According to Edmund

Mitchell Crosse's grandson Noel Crosse, Mary Louisa had a drink

problem, and this may partly account for her early death.

Mary

Louisa Clabburn (1850-1886) married

Edmund Meridith Crosse

(1846-1918) of the Crosse & Blackwell tinned

food manufacturing firm,

and had five children. Mary died just three years after giving birth to

their younger son Edmund

Mitchell Crosse (b. 1883), who later married Leda Roumieu,

grand-daughter of the architect R. L. Roumieu (1814-1877). Roumieu

had designed warehouses for the Crosse and Blackwell firm and Leda's

aunt

Emilie Isabella Roumieu (1852-1929) had been an early love of Mary

Louisa's elder brother Arthur's [CLA/16],

though she had gone on to marry (and subsequently divorce, on grounds

of

adultery and violence) Alexander Coghill Wylie. According to Edmund

Mitchell Crosse's grandson Noel Crosse, Mary Louisa had a drink

problem, and this may partly account for her early death.

Walter

Thomas Clabburn (1851-1908) possibly has the saddest story

of any of

the Clabburns. Sandys made a chalk drawing of him, age 20, in

1871 (CLA-29

no. 3.24 - now at Norwich Castle Museum), when the census recorded him

as a brewer, but he seems to have had difficulty in settling to a

career. The following year he was

commissioned as an Ensign in the 1st Norfolk Volunteer Rifle

Corps. He did not remain in the army for long and I have not

yet investigated the possibility that he may have served with the Cape

Police in South Africa, but by the late 1890s he was a gold-miner in

Western Australia. This does not seem to have made his fortune, but he

stuck at it. In February 1908 he was involved in a dispute with a local

storekeeper over an unpaid bill for £18 14s 3d, but told a

neighbour

that he had receipts and was confident that he would win the court case

in the local town of Morgans. When he failed to turn up at court,

judgement was given against him by default, and the local constable

then went to his camp, where he lived alone. There he found that Walter

had placed dynamite in his mouth and blown his own head off. He is

buried

in the cemetery at Mount Morgans, and the subsequent administration of

his (intestate) estate valued it at just £25. Presumably news

of his

death, and the circumstances, reached his family in England, but other

than a note of "died in Australia", there seems to have been no mention

of

it in the family's oral history, and I have uncovered the story from

contemporary newspaper reports [CLA/30].

Walter

Thomas Clabburn (1851-1908) possibly has the saddest story

of any of

the Clabburns. Sandys made a chalk drawing of him, age 20, in

1871 (CLA-29

no. 3.24 - now at Norwich Castle Museum), when the census recorded him

as a brewer, but he seems to have had difficulty in settling to a

career. The following year he was

commissioned as an Ensign in the 1st Norfolk Volunteer Rifle

Corps. He did not remain in the army for long and I have not

yet investigated the possibility that he may have served with the Cape

Police in South Africa, but by the late 1890s he was a gold-miner in

Western Australia. This does not seem to have made his fortune, but he

stuck at it. In February 1908 he was involved in a dispute with a local

storekeeper over an unpaid bill for £18 14s 3d, but told a

neighbour

that he had receipts and was confident that he would win the court case

in the local town of Morgans. When he failed to turn up at court,

judgement was given against him by default, and the local constable

then went to his camp, where he lived alone. There he found that Walter

had placed dynamite in his mouth and blown his own head off. He is

buried

in the cemetery at Mount Morgans, and the subsequent administration of

his (intestate) estate valued it at just £25. Presumably news

of his

death, and the circumstances, reached his family in England, but other

than a note of "died in Australia", there seems to have been no mention

of

it in the family's oral history, and I have uncovered the story from

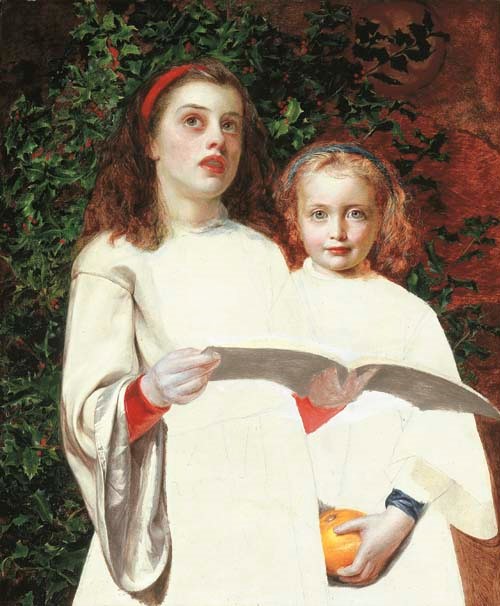

contemporary newspaper reports [CLA/30].![Lucy Clabburn drawing by Sandys [Elzea 2.A.41] Lucy Clabburn drawing by Sandys [Elzea 2.A.41]](Sandys%20Lucy%20Clabburn.jpg) Lucy

Clabburn (1856-1914), aged about 5, appears with her elder

sister Mary in

Sandys' At

Vespers (above), and Sandys made another drawing of her

at around the same time, which was sold at Sotheby's in 1981 as "Study

of

a Little Girl's Head" [CLA/29, no. 2.A.41] (near right).

In the early

1870s,

her brother

Arthur

made a

crayon portrait of her (far right), in which Norwich Castle and

Cathedral appear in

the background. Arthur had been

serving in the army, and was posted abroad from 1868. Surviving

correspondence [CLA/16/2]

shows that he was at home on leave in late

1871, and he was put on the "half pay" (reserve) list in July 1872,

when Lucy would have been just 16. From the apparent age of the sitter,

the picture probably dates from

then. As he tried to establish himself as an artist, Arthur was

befriended

by Sandys, and it is probable that he received some training from him.

The portrait remains in the possession of my sister

Anne Barnard who, as a child, bore a striking resemblance to

her great-great-aunt; the same is

supposed to have been true of our mother.

Lucy

Clabburn (1856-1914), aged about 5, appears with her elder

sister Mary in

Sandys' At

Vespers (above), and Sandys made another drawing of her

at around the same time, which was sold at Sotheby's in 1981 as "Study

of

a Little Girl's Head" [CLA/29, no. 2.A.41] (near right).

In the early

1870s,

her brother

Arthur

made a

crayon portrait of her (far right), in which Norwich Castle and

Cathedral appear in

the background. Arthur had been

serving in the army, and was posted abroad from 1868. Surviving

correspondence [CLA/16/2]

shows that he was at home on leave in late

1871, and he was put on the "half pay" (reserve) list in July 1872,

when Lucy would have been just 16. From the apparent age of the sitter,

the picture probably dates from

then. As he tried to establish himself as an artist, Arthur was

befriended

by Sandys, and it is probable that he received some training from him.

The portrait remains in the possession of my sister

Anne Barnard who, as a child, bore a striking resemblance to

her great-great-aunt; the same is

supposed to have been true of our mother.

![James Blyth (Henry James Catling Clabburn) [CLA-61-29] Photo of James Blyth](Clabburn_Images/CLA-61-29%20James%20Blyth%20Photo.jpg) Henry James Catling Clabburn

(1864-1933),

was by a considerable margin the youngest of his parents' six children,

and

recent research has shown him to be one of the most interesting, if not

necessarily the most sympathetic, of my Clabburn forbears. He was the

only one to receive a University education and, after a short career as

a solicitor in London, a scandalous divorce case brought by his wife Margaret Rebecca Rance (1868-1954) forced him to retire

back to rural East Anglia, where he changed his name to James Blyth and

spent nearly 25 years as a prolific author, mainly of romantic novels

set in the Norfolk marshes. One of these, Celibate Sarah,

is

significantly autobiographical and features thinly disguised portrayals

of many members of his extended family, who are treated most

uncomplimentarily, not to say libellously. In the early 1920s he

returned to London and taught at the newly-established London School of

Journalism.

Following the divorce case (which resulted only

in a legal separation from his wife), he spent the rest of his life with Rachel

("Ray") Ockelford (who also changed her surname to Blyth), but he had no

children from either relationship.

Henry James Catling Clabburn

(1864-1933),

was by a considerable margin the youngest of his parents' six children,

and

recent research has shown him to be one of the most interesting, if not

necessarily the most sympathetic, of my Clabburn forbears. He was the

only one to receive a University education and, after a short career as

a solicitor in London, a scandalous divorce case brought by his wife Margaret Rebecca Rance (1868-1954) forced him to retire

back to rural East Anglia, where he changed his name to James Blyth and

spent nearly 25 years as a prolific author, mainly of romantic novels

set in the Norfolk marshes. One of these, Celibate Sarah,

is

significantly autobiographical and features thinly disguised portrayals

of many members of his extended family, who are treated most

uncomplimentarily, not to say libellously. In the early 1920s he

returned to London and taught at the newly-established London School of

Journalism.

Following the divorce case (which resulted only

in a legal separation from his wife), he spent the rest of his life with Rachel

("Ray") Ockelford (who also changed her surname to Blyth), but he had no

children from either relationship.

In addition to the individual

portraits, five of William

Houghton Clabburn I's children (Henry was not yet

born) were the models used in Sandys' Study for Spring

(1860) [CLA/29,

no. 2.A.35]. Though it's difficult to assess the ages of the

figures in

the picture in order to identify them individually, my guess would be

that, from left to

right, they are Walter (9), William (12), Lucy (4),

Mary (10,

leaning over), and Arthur

(11, with the closest resemblance to the photograph of him shown

above). In her catalogue

raisonné [CLA/29] Betty Elzea reverses the

identification of William and Walter. This

drawing is now at Norwich Castle Museum, and may have been a study for

an oil painting that cannot be traced, and indeed might never have been

painted, though Elzea gives it a catalogue number of 2.A.36.

In addition to the individual

portraits, five of William

Houghton Clabburn I's children (Henry was not yet

born) were the models used in Sandys' Study for Spring

(1860) [CLA/29,

no. 2.A.35]. Though it's difficult to assess the ages of the

figures in

the picture in order to identify them individually, my guess would be

that, from left to

right, they are Walter (9), William (12), Lucy (4),

Mary (10,

leaning over), and Arthur

(11, with the closest resemblance to the photograph of him shown

above). In her catalogue

raisonné [CLA/29] Betty Elzea reverses the

identification of William and Walter. This

drawing is now at Norwich Castle Museum, and may have been a study for

an oil painting that cannot be traced, and indeed might never have been

painted, though Elzea gives it a catalogue number of 2.A.36.

Hannah died, aged just 53, on 6 March 1878, but

William lived on for another eleven years, dying on 10 July 1889, a few

months after his 69th birthday. A local newspaper obituary [CLA/35] noted

that he had just been re-elected as a Director of Norwich Union

Insurance, though had been unable to attend meetings due to illness.

They are buried together in Earlham Cemetery in Norwich [CLA/36]. An

article in a Norwich magazine in 2021 by local historian Robert Wenn [CLA/38] comments

that the grave plot is unexpectedly large for just two people - perhaps

he had originally intended that some of his children might also be

buried there, but by the late 1880s they were scattered far and wide,

and any hopes he might once have had that they would emulate his own

successful business career as one of the "men who made Norwich" [CLA/40] were not

fulfilled.

Hannah died, aged just 53, on 6 March 1878, but

William lived on for another eleven years, dying on 10 July 1889, a few

months after his 69th birthday. A local newspaper obituary [CLA/35] noted

that he had just been re-elected as a Director of Norwich Union

Insurance, though had been unable to attend meetings due to illness.

They are buried together in Earlham Cemetery in Norwich [CLA/36]. An

article in a Norwich magazine in 2021 by local historian Robert Wenn [CLA/38] comments

that the grave plot is unexpectedly large for just two people - perhaps

he had originally intended that some of his children might also be

buried there, but by the late 1880s they were scattered far and wide,

and any hopes he might once have had that they would emulate his own

successful business career as one of the "men who made Norwich" [CLA/40] were not

fulfilled.

William's Will [CLA/10], dated eight months before his death, is an interesting document on account of the different legacies (and terms applied to them) for his different children, though it gives the lie to the idea that any of them was "cut off without a shilling" due to paternal disapproval [CLA/2/1]. He had by then been a widower for some ten years, and his elder daughter Mary Louisa was also dead, though his youngest son Henry had only fairly recently graduated from Cambridge, and was working as a solicitor in London. His eldest two sons, William and Arthur, were both married with children. The shawl-making business, if it was still going at all by then, was clearly in decline, and whilst William was still comfortably off, his fortune was no longer nearly as substantial as it had been in the 1850s and 1860s.

- He evidently trusted his youngest son Henry, who was made one of the Executors and Trustees, and also received the largest legacy of any of his sons (about £780, equivalent to about £100,000 in today's terms).

- William, the eldest, (in New Zealand) received a gold watch and the interest on £500, but only for as long as he was not bankrupted, and he was not to have access to the capital, which was reserved for his children.

- Arthur, by then a struggling artist, got £300 (about £37,000 in today's terms) and the benefit of a life assurance policy his father had taken out with Norwich Union (presumably to ensure that there was some provision for Arthur's children, of which there were now four, in case of his early death). This would certainly have been a big help to Arthur's finances, but wouldn't have left him financially independent.

- Walter got just £200 (£25,000 in today's terms) which perhaps paid for his travel to Australia and allowed him to set himself up as a gold prospector.

- There was no provision for Mary's children, though as their father was a senior partner in the Crosse & Blackwell tinned food firm, they were probably pretty well provided for.

- The bulk of William's estate, in the shape of nearly £700 in cash, and a trust fund of £4,000, was left to Lucy, with stipulations to ensure that no spendthrift husband she might marry could get his hands on the capital, or even the interest, of the trust fund. This left Lucy comfortably off as a "lady of independent means". She had the power to bequeath the capital of the trust fund in her own will, and (apart from £50 and the gardening tools to her gardener) everything was left to her partner of at least 33 years, Clara Shardelow [CLA/12].

Thomas Clabburn III (1824-1880)

![Thomas Clabburn III Portrait by Charles Croft [CLA/44/2] Thomas Clabburn III Portrait by Charles Croft [CLA/44/2]](docs/CLA_Docs/CLA-44-2%20Thomas%20Clabburn%20III.jpeg)

![Blanche Elizabeth Clabburn [CLA/44/3] Blanche Elizabeth Clabburn [CLA/44/3]](docs/CLA_Docs/CLA-44-3%20Blanch%20Elizabeth%20Clabburn.jpeg) Thomas (left) was the second

surviving son of Thomas

Clabburn II, and

joined his father and elder brother, my great-great-grandfather William

Houghton Clabburn I,

in the shawl manufacturing firm of Clabburn Sons and Crisp. Quite what

role he played in the business is unclear, as William clearly became

the driving force behind it after their father's death, but he was

financially successful and purchased the large Lammas Hall about ten

miles north of Norwich for his own occupation.

Thomas (left) was the second

surviving son of Thomas

Clabburn II, and

joined his father and elder brother, my great-great-grandfather William

Houghton Clabburn I,

in the shawl manufacturing firm of Clabburn Sons and Crisp. Quite what

role he played in the business is unclear, as William clearly became

the driving force behind it after their father's death, but he was

financially successful and purchased the large Lammas Hall about ten

miles north of Norwich for his own occupation.

Perhaps following the example of his brother, he commissioned portraits of himself, his mother and his daughter from an artist called Charles Croft [CLA/44]. I have been unable to find any other information about Croft or his paintings, and he did not have the distinguished career of William's protegé Frederick Sandys. He is probably the Charles Croft recorded with his wife Hannah at Swaffham in Norfolk in the 1861 census, though I have not been able to identify him in any other censuses, nor in birth, marriage and death records.

Thomas married Betsy Blanch Goold (1832-1894) at Erpingham in Norfolk in 1851, and they had four sons and a daughter. There are Clabburn descendants (including Michael Clabburn) of at least one of the sons, while the daughter, Blanche Elizabeth Clabburn (1859-1937) (right, as a child) went on to marry Hugh Paston Mack (1857-1933) of Paston Hall in Norfolk. All three of the Croft portraits are now owned by their grandson Tom Rivière, who has kindly provided the images shown on this page.

Robert George Clabburn (c. 1828 - 1863): dental surgeon and serial bankrupt

All families have their "black sheep" and Robert George seems to have been the Clabburns', at least in this generation. He was the third surviving son of Thomas Clabburn II (1788-1858), and eight years younger than his brother, my great-great-grandfather William Houghton Clabburn I. He does not seem to have taken an interest in the family shawl weaving business, and pursued a career as a dental surgeon, though this somewhat marred by a tendency to regular appearances in insolvency courts on both sides of the world.

There is no baptism record for him, but his age on his marriage record, dated 15 Sep 1849, is given as 21. His bride was a Norwich girl, Mary Jane Fulcher (b. 1831), but the wedding took place in East London rather than in their home town. They appear in the 1851 census in Melcombe Regis, Dorset, along with a one-year-old son Robert William Clabburn (born in Weymouth in the first quarter of 1850, less than six months after his parents' marriage, suggesting that it may have been a bit of shotgun wedding). Robert George is shown as the head of the household, with occupation "surgeon dentist", and there are no less than four servants listed: either his wife came with a very substantial dowry, or they were living beyond their means. A second son, Thomas Herbert Clabburn was born later in 1851, and baptised in Weymouth on 26 May, but died there that summer.

By March the following year Robert George was back in Norwich, but this time in the Debtors' Gaol, and he appeared before the insolvency court in the city on 6th March 1852 [CLA/28]. Mary Jane was pregnant again, and a daughter Anna Clabburn was born on 10th June. With business booming following the Great Exhibition the previous year and shawl sales being made to Royalty, all this was no doubt something of an embarrassment to his father and brothers, who were now pillars of Norwich's Victorian establishment. It is easy to imagine Thomas Clabburn II paying off his son's debts, packing him off on the first boat to Australia, and telling him not to come back. Certainly, Thomas's Will, written in 1856 (he died in 1858) contains a specific provision that certain reversionary funds be bequeathed to "such child or children of mine then living ... other than and except my son Robert George Clabburn"; Robert George receives no other mention in the Will [CLA/9].

At any rate, the Melbourne Argus for 13 Dec 1852 reports the arrival from London of the Gloriana carrying "Mr and Mrs Clabburn and family". On 9 July 1853, the Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer carries a notice that "Mr Clabburn, Surgeon Dentist respectfully announces to the inhabitants of Geelong that he may be consulted on Friday and Saturday the 15th and 16th inst." The following January he went into partnership with a Mr L.A. Beurteaux, but the partnership was dissolved by mutual consent in April, and Robert George continued to advertise his services on his own account.

However, an unfortunate incident involving a forged signature on a bill of exchange for £50 led to Robert George's appearance at the Geelong Assizes on 26 October 1854, charged with forgery and uttering a forged document. The evidence was somewhat confused and the jury almost immediately returned a "not guilty" verdict. Whatever the facts of the case, this wouldn't have done Robert George's reputation in Geelong any good, and a week later he was advertising his services in Launceston, Tasmania, where he spent the rest of his life.

Sixteen months later, in April 1856, he was back in court again, being sued for a debt, and by June he was again insolvent. At hearings before the local Commissioner on 23rd July and 6th August it was claimed that he "hardly paid a debt without being sued" and he was questioned on his "habits of life" and expenses at the Club Hotel. Robert George denied extravagance, though he admitted to having had some champagne etc. on his son's birthday (Robert William would have been six earlier in the year). He denied that he had been "gambling in the ordinary sense of the term", which does sound somewhat disingenuous. As he could show an income of £600 a year from his dental work, and thus had a good prospect of repaying his debts, he was discharged.

A

question

remains over what happened to Robert George's wife Mary Jane. A search

of the local papers reveals no death notice for her, but on 11 August

1857 Robert George (age given as 30) married 17-year-old Annie Bland in the

Wesleyan chapel at Longford, just south of Launceston; he is described

in the register as a bachelor. A son (not named in the register) was

born on 31 Mar 1860.

Robert George continued to make intermittent appearances in the insolvency court, and even in the police court on 20 Aug 1862 when he tried to have one of his creditors bound over for threatening him with assault. The magistrate recognised that the threats were "not of a very serious or vindictive nature" and added 3/- costs to the debt.

He also seems to have developed a macabre fascination for the skulls of executed criminals, often turning up at hangings for the purpose of taking casts of their heads, and sometimes even gaining possession of their skeletons. This interest appears to have been related to the Victorian pseudo-science of phrenology in which lumps and bumps on the skull were supposed to be indicative of criminal tendencies, and an article in the Cornwall Chronicle for Launceston on 11 Jan 1862 lists some of the notorious murderers in his collection.

Robert George's career was brought to a halt on 10 Sep 1863 when he died of consumption (tuberculosis), aged only 35; whether he contracted the disease from a patient, or from one of the executed criminals with whose remains he had such intimate contact, must remain a mystery. His widow Annie arranged for his dental practice to be sold, and in 1870 she remarried, to George Theophilus Shillington. Robert's "relatives in England, who are highly respectable" agreed to maintain his son Robert William (age 13 when his father died) until he was old enough to choose a profession - there is some irony in the fact that the local trustee they chose was Mr W. G. Sams, the Commissioner who oversaw most of Robert George's insolvency cases. Tragically, Robert William was drowned, age 17, after falling overboard from the schooner Governor Wynyard on 15 March 1868 [CLA/28].

At this point his sister Anna Clabburn seems to have returned to England, because she was baptised at St Augustine's Church in Norwich on 17 Sep 1868 (some secondary sources have misinterpreted this as her birth date, but she was now 16, and the parish register shows her actual birth date). What happened to her after that is uncertain, as I have found no record of her marriage or death.

It is possible that Robert George's son by his second marriage, unnamed in the Tasmanian birth record, has living descendants in Australia, but it is difficult to try to trace any marriage or death for him without a name.

Other Clabburn Families in Norwich

The weavers and shawl manufacturers described above were not the only prominent Clabburn family in 19th century Norwich. James William Clabburn (1843-1918) was Mayor of the city in 1899, and his granddaughter Pamela Clabburn MBE (1914-2010) was a curator at the Strangers Hall Museum in Norwich, and did much work on the history of shawl-weaving in the city. She was contacted by Marcus Clabburn (1929-1971), an Australian grandson of Arthur Edward Clabburn, when he visited Norwich in the 1950s, by the simple expedient of looking up "Clabburn" in the telephone directory, and she remained in contact with Marcus and his widow for many decades thereafter. It is probable that the two families are related, though any common ancestor is almost certainly back in the early 18th century, or even earlier.

Michael Clabburn (1948-2004), a descendant of Thomas Clabburn III, did some genealogical work in the 1980s and 1990s, attempting to link the Norwich Clabburns to the Claibourne family living in Westmoreland in the 16th century and before, but with links to Claibournes in Kings Lynn and in the colony of Virginia. No definite link seems to have been established, but Michael corresponded extensively with my uncle Bob James in the 1990s and I have not yet studied the papers in detail [CLA/4]. I am now in contact with Michael's youngest son Oliver Clabburn, who retains all his father's papers.